By Andrew McCarty Grossen

This week The Atlantic’s Emma Green published an interview with Fr. James Martin in which they discussed his argument that “anti-Catholicism is the last acceptable prejudice”. But do instances of mocking and criticizing Catholicism in some circles reflect the American public’s views and attitudes towards Catholicism in such a way that would warrant the title of “anti-Catholicism” as the “last acceptable prejudice”? Recent data would suggest it does not, especially compared to American prejudices towards atheists and Muslims.

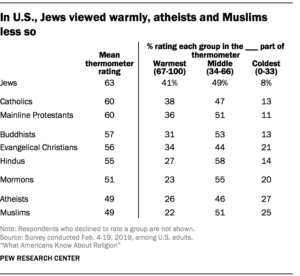

One straightforward indicator on how Americans feel towards various religious groups* is Pew Research Center’s “feeling thermometer” which was most recently used in a 2019 survey. Respondents rated groups from 0 to 100, with the higher the number the warmer (more favorable) that group is viewed. Catholics are consistently viewed among the warmest just behind Jews while atheists and Muslims are rated the coldest (60 degrees versus 49 degrees, respectfully). Also notable, just as many people rate atheists at the coldest end of the scale (33 degrees or below) as rate them at the warmest end of the scale (67 or higher). Additionally, Pew has found that 63% of Americans have a favorable view of the current Pope. On the surface, Catholic Americans are viewed much more favorably by wider society than others, especially atheists.

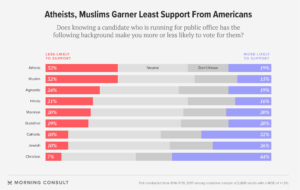

These ‘warm’ and ‘cold’ feelings are reflected in other polling data. In 2017, an online poll conducted by Morning Consult found that 32% of respondents said they were less likely to support a candidate from a Muslim or atheist background. Compare that to the 10% who said they were less likely to support a Catholic candidate. Interestingly, a hypothetical Catholic candidate seemed to be a motivator for support from poll respondents at a rate much higher than atheists or Muslims. Indicating that a candidate’s Catholic background might actually help their public perception while running for office. These attitudes are inextricably connected to prejudices and misconceptions towards atheists and Muslims and that can not be ignored.

It’s not just hypothetical Catholic candidates who receive support from the American public. Catholic Americans have disproportionate representation in public office at the federal level. Currently, 157 Catholics are Members of Congress, which is roughly 29% of the entire U.S Congress. They are also members of both parties with both the Speaker of the House and the Minority Leader sharing Catholic faith. Contrary to what some commentary one would read, Catholics make up a higher share among Democrats than they do among Republicans in Congress. Additionally, six out of the nine Supreme Court Justices are Catholic and at the state-level, 16 Catholics are currently governors of states, the most of any individual religious group. Finally, and maybe most notably, the sitting president is Catholic as so are many of his aides and appointees. If anti-Catholicism exists in a real sense, data would suggest it does not seem to be a barrier to public life.

Meanwhile, despite religiously unaffiliated Americans making up over a quarter of the US population, only two sitting Members of Congress identify as either religiously unaffiliated or nontheist. Additionally, there has never been an openly nontheist president or Supreme Court Justice. Anti-atheist prejudices are no doubt a factor in all of this. Accusations that atheists are immoral, insular, antitheist, unkind, or un-American remain pervasive in our discourse even as studies show that atheists “hold less animosity toward Christians than Christians hold toward them”. Rooted in these prejudices are laws that still exist in 7 states that ban atheists from holding office. While not Constitutionally enforceable, we should take seriously how anti-atheist prejudice remains a significant barrier to those seeking public office.

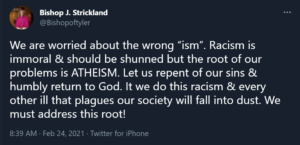

Most disturbingly, anti-atheist prejudices are displayed publicly by elected officials without much pushback from the wider media and political community. Examples are numerous but include former President Trump, Rep. Doug Collins, Rep. Markwayne Mullin, Rep. Paul Gossar, Rep. Mike Johnson, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn. As discussed by Martin and Green, there were highly publicized debates around charges of anti-Catholicism leveled at Senators during recent Supreme Court nominations. However when atheists and the “godless” are disparaged by Clergy and Congressperson, there is universal silence, even from the “secular” and “liberal” media outlets. Rarely does our country ask “why anti-atheist prejudice is prevalent in our society?”

Martin, to his credit, does acknowledge that cries of anti-Catholicism are too frequent and subjective, but his doubling-down on the label of anti-Catholicism as the “last acceptable prejudice” is not justified by an analysis of American views towards Catholics. The Atlantic’s failure to engage with this broader context only perpetuates a distorted view of the prejudices faced by different communities in this country and continues the silence around anti-atheist prejudice.

Is it fair to ask why Catholics face prejudice in secular circles and not ask why atheists face prejudice at higher levels in religious circles?

The overused online adage “Twitter is not real life” does seem appropriate for all of this. While a New York Times review or tweet from an atheist organization might appear to be “anti-Catholic” this does not mean that anti-Catholicism is a prevalent issue that has tangible consequences for the vast majority of Catholic Americans, especially in political spaces.

We appreciate that Fr. Martin asks Americans to approach topics like contraceptives, abortion, sexuality, and religious freedom, with respect and understanding in order to have healthy debate. As secularists who engage in criticism of powerful and deeply-rooted religious institutions and beliefs, we absolutely agree. It is necessary to ensure that our criticisms are rooted in facts and accuracy free from falsehoods but we also ask that respect and understanding is mutual both from those in religious communities and from the media. If anti-Catholic prejudice essentially amounts to mocking or irreverently criticizing Catholicism, we’d ask institutions secular and religious to consider how they might engage in anti-atheist prejudice.

It is not our intent to declare that anti-atheist prejudice is the “last acceptable prejudice” but rather call for an honest engagement with facts and broader context of how different groups are viewed and treated in American society as this is necessary if we are to overcome bigotry and misconceptions.

* While atheists, agnostics, nontheists, and others who are nonreligious are not technically a “religious group” since Pew and other publications group them as such for the purposes of this blog post, I did the same for clarity.

Andrew McCarty Grossen is the Communications Manager for the Secular Coalition for America. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of the Secular Coalition for America as an organization.