By Andrew McCarty Grossen, Communications Manager, Secular Coalition for America

As today is St. Patrick’s Day, which is celebrated both religiously and secularly throughout the world, I would like to take this opportunity to share with you my reflections on what Ireland showed me regarding secularism during my life there which spanned from 2012 to 2019.

I had only been living in Ireland for two months before the death of Savita Halappanavar. A woman who was denied her request for an abortion following an incomplete miscarriage on the grounds that granting her request would be illegal under Irish law, ultimately resulting in her death from septic miscarriage. To explain the context of Ireland’s laws prohibiting abortion in most cases she was told “Ireland was a “Catholic country”.

Savita’s death was one of the first major news events that I experienced in Ireland, and it brought to the forefront topics of conversation that have been long been controversial, not just about abortion, or general reproductive rights but also the relationship between the Catholic church and the Irish state.

This relationship has a long, complex, and all too painful history, from recognizing a “special position” of the Catholic Church in the original Irish constitution to religious authorities who wielded undemocratic political and societal power. The state in its early years essentially legislated Catholic doctrine regarding contraception, homosexuality, divorce, obsentity, and blasphemy. It would relegate entire sectors of society like education and healthcare to the Church’s domain, leaving Ireland’s most vulnerable to the institutions that lacked transparency, oversight and accountability.

By the time I got to Ireland in 2012, the worst of Ireland’s religious oligarch’s crimes were already committed, the extent and details were still being realized, and justice for victims remained still far out of reach. As Ireland became a more open society, so did its institutions, and those that demanded oversight and justice were shining a light into the decades of darkness. A steady flow of state authored reports on the abuses of the church and its affiliates would bring about an era of very public reckonings with the relationship between church and state.

Savita’s death would serve as a personal bookend of that era, of which I was both a witness and occasional participant in. However, the fight for legalized abortion would continue on for another half decade. Yet, the fight for marriage equality was also confronting the past political power of the church and testing whether that power still had salience in 21st century Ireland. Like other social movements I witnessed in Ireland, I saw but one chapter of the campaign for marriage equality, but it was indeed an exciting one.

The national referendum which the question of legalized same-sex marriage would be decided in was in my first year of college. I recalled the feeling of anxiety and helplessness that I experienced a few years prior as I sat in front of a computer in Cashel, Tipperary, refreshing the browser, awaiting the results from my home state of Minnesota’s referendum on whether the state constitution should define marriage as between one man and one woman. I did not want to be passive this time around. Even though I did not have a vote, I had a voice, one that was still quiet about my sexuality, so joined the campaign with my university’s student union, UCDSU.

It was empowering to see young people of all party affiliations standing up for the rights of others. When the day finally came and the results announced, they could not be more uplifting. The pure joy I experienced that day in May, seeing the cheering and crying crowds in rainbow clad Dublin, solidified what I loved about Ireland and what Ireland meant to me.

It defied the conventional thinking and views of Irish America’s many conservative members who often romanticize “the Old Country” as the pinnacle of Catholic piety. As celebrations erupted in all parts of the island, Irish Americans, looked on with dismay. Some viewed this as the beginning of the end of Catholic Ireland, which honestly, held some truth.

Unfavorable views of the Church were increasing, Mass attendance was in freefall, both in part because facts that were once secrets were secrets no longer. They had tried to influence the debate in the lead up to the referendum, but their overwhelming defeat at the ballot box showed the world their political capital was the weakest it has ever been since the founding of the Republic. In everyday life, this was evident. There seemed to be a feeling that Ireland was finally ready to join the majority of European and North American nations that respected basic rights and dignities. Marriage equality was achieved, could legalized abortion be next?

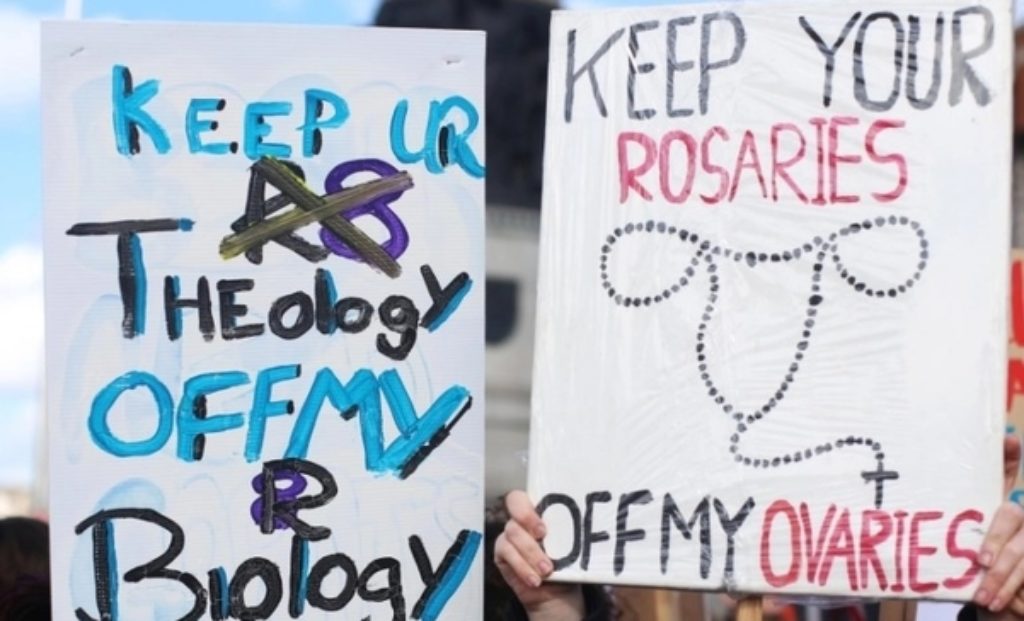

Nobody was naive to the legal and political challenges that laid ahead, but there was a sense those challenges could be overcome and one of the biggest obstacles of the past, the Church, no longer had the strength to be influential in the matter. It wasn’t just pro-choice advocates who knew this, the Church did too.

In the referendum to repeal the Constitutional Amendment which prevented legalized abortion, the church stepped back and was less vocal than in previous years out of fear of causing further harm to their agenda. Yet, even a more secular anti-choice campaign, still with highly religious undertones, could not prevent another blow to their influence and relevance. In May 2018, Ireland voted in favor of repealing the Eighth Amendment, opening the door for legislation legalizing abortion.

The following year another referendum was held, one that carried little attention or fanfare but was yet another win for human rights, a repeal of Ireland’s blasphemy laws. It was almost a rubber stamp in the process of Irish secularization that continues to this day with current plans to address religion’s role in hindering science-based sex-education in public schools. One political party, the Social Democrats, even have a plan to hold a “Citizens Assembly” on the relationship between religion and society, should they be elected into government.

Irish society is undoubtedly changing but it still is having to reckon with the trauma of the past, and present, brought on by powerful institutions that have yet to be held truly accountable. This trauma and pain caused by abusers within church and state was not inevitable.

We in America, including “Irish America” should learn from Ireland’s past and present and work to prevent similar abuses from taking place even if our political and religious landscape is vastly different. We had no Magdalene Laundries or Mother and Baby Homes but religious abuse is no stranger here. It has a long history of being enabled by state actors inappropriately using their power. I have come to see Ireland as a case-study of the dangers posed by religious institutions being granted expansive political power. Our public institutions and civic society must hold power to account and demand transparency and accountability. Religious institutions accepting public resources while seeking exemptions from our laws remains a dangerous precedent. Religious freedom is incredibly important to a healthy democratic society but religious freedom must not be weaponized.

There are also lessons to be found in the consequences of linking secular national identity to religious affiliation. The idea that Catholicism was linked to Irishness generated a defensiveness that saw criticism of the former as an attack on the latter, causing a willful ignorance to very real abuses, including here in America. This bears a striking resemblance to reaction towards condemnations Christian nationalism here in America. Not only is the understanding of America as a “Christian nation” historically and factually wrong, it enables Christian supremacy. It helps Christian institutions from being held accountable when abuses occur. (It is no surprise that many Americans still link “godlessness” with being unpatriotic).

As individuals and organizations that seek to maintain the separation of religion and government; Ireland, through its national referendum campaigns also gives us political lessons. The coalition building and campaign strategies that were required to have a successful national referendum in favor of marriage equality and legalized abortion, have immense educational value for those of us stateside. These campaigns took place in communities that even though religious affiliation was rapidly declining, there were still a high degree of theism. An identical phenomenon we see in the US.

As nontheists, we can learn how to protect and strengthen secularism while respecting and upholding religious pluralism. Today (ironically, given that today’s holiday springs from a Catholic Saint’s Feast Day) can be an opportunity to do just that. By celebrating Irishness that is not tied to one specific church, but a people of many beliefs including many nontheists, we celebrate the Ireland I know, the Ireland I love, the Ireland that continues to grow; one of LGBTQ+ rights, of reproductive rights, of secularism and religious pluralism.